Fourteen Painters Give Us a Glimpse of

CONTEMPORARY BRITISH PAINTING

Canadian Art (no. 91) (May/June 1964)

[Regrettably the space allotted by the journal limited the number of artists discussed or illustrated. However, for this version I have been able to add to the illustrations. The title of the essay was not mine.]

In June last year [1963] London was treated to an enormous review of contemporary British painting. So many artists were represented that the Arts Council of Great Britain reserved the Tate Gallery space exclusively for painters over age 35 and had to employ the Tate’s sister gallery at Whitechapel to house the rest. Even then some significant artists had to be omitted. So visitors to the small exhibition just completing a tour of seven Canadian cities should understand the scale and range signified by the big show and realize that the 14 painters to be seen here were selected according to a quite narrow principle. They were, that is to say, all leaders of the avant-garde ten years ago, and with some exceptions, made a group mostly by having lived at some point in their lives in the same Cornish fishing village or by having taught at the same academy of art in rural Wiltshire [see further information on the artists, added at the end of the essay].

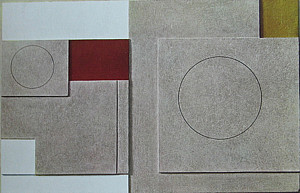

Ten years ago, for such artists, leading the avant-garde in Britain meant going painterly, and except for Nicholson; Sutherland and Pasmore who still hold to the aesthetics of the 1930s, this is the characteristic that distinguishes the work shown here from more recent fashions. The visitor will also realize that he has been confronted with a concern, however attenuated, for other familiar matters: for checks and balances, for qualities of light and concepts of space, for the sensuous impact of colour and of regressive line—besides la belle matière. True, these concerns can sometimes be appraised in the light of a preoccupation with existential meaning—with the throw-away handling that appeared in the United States nearly two decades ago – but such concerns have by now become part of the fine art canon from which the avant-courier on both sides of the Atlantic has successfully broken free, and what once looked like a broad front has been widely outflanked, by irony, nostalgia, a sort of positivism and Boccioni’s “vortex of modern life,” unless, as in the work of Patrick Heron’s shown here, we find the echo of a friendship with the American critic Clement Greenberg and his promotion of “Post-painterly Abstraction.”

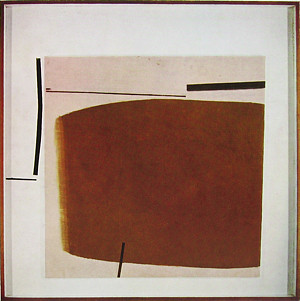

Disc and Black Column, (1960)

with Violet Edge, (1965)

On the whole, then, this is not a difficult exhibition. The light in Nicholson, Pasmore, Scott, Lanyon or Mundy goes back at least to Turner; Lanyon’s anti-handling brio to Venice even, Scott’s to Bonnard, and Mundy’s to the rococo, whilst Nicholson’s line is by way of Ingres from the quattrocento, Sutherland’s iconography has roots in the middle ages and Wynter’s calligraphy in Japan.

Such parallels are not perhaps of vast importance, but they give the spectator a way in which these works can be approached. Certainly they should not be understood pejoratively. On the contrary, this is a rich exhibition and those prepared to do homework on it will be rewarded. In this respect I wonder how many visitors in Toronto were directed to the pictures by those three of these artists that the Art Gallery of Toronto already owns (The Sutherland of 1949 and the Nicholson of 1950 reveal how little the ambit of these two has changed, but the 1955 Scott Still Life, in contrast, shows how far and how consistently Scott’s paradox has traveled in ten years—how much he has gained from his carefully contemplated rejections as in the following three works. (1)

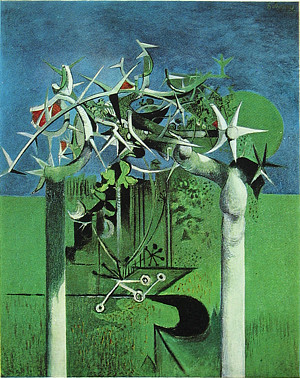

Of course, Sutherland’s change of register came earlier than the Art Gallery of Toronto painting, around the first years of the Second World War. At that time he was painting water-colours of astonishing timbre, and his line showed a tendency to the subtle awkwardness which Hilton and Scott have so successfully exploited since. But he became more firmly figurative, to a considerable extent renouncing his colour and line in preference for sculptural, monumental forms, and entered that airless world of discomforting lumps and castratory thorns, from which he has rarely managed to escape.

Of other painters, only Bacon invites the same repelling fascination, but Bacon’s is a world that assaults the nerves where Sutherland’s grotesque vegetables threaten the bowels, or at least the best of them do, for Sutherland’s gilt-edged science fictions have not always escaped the blight; there is sometimes a failure of scale—which in the pre-war period achieved uncanny ambiguities, as in Thorn Trees, of 1936.

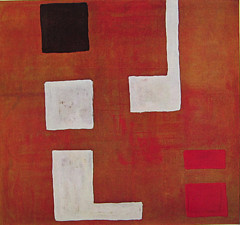

Nicholson, the most revered English painter of the century, has never faltered, and the works here, spanning thirty years, indicate his extraordinary conviction. But they cannot hint at his enormous productivity, or the unending richness that he finds in so puritanical a compass.

[Nicholson won the Guggenheim prize in 1956]

Nicholson may be seen until the Fifties as Britain’s most extreme painter. He is not himself a heavy theorist, but he associated with the extreme purists of the 1930s and collaborated at that time in the production of Circle, a book propagating the constructivist gospel. Even so, he has kept himself aloof from the machine aesthetic with which the constructivists flirted and mellowed their severity—anchoring their absolutism to the Cornish landscape in which, for most of his life, he has lived.

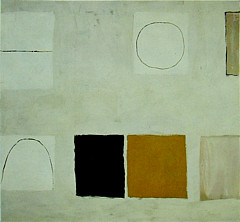

Post-war art in England begins with Victor Pasmore. Circle had existed ten years (six of them war years) when Pasmore, whose face had been set against non-figuration, announced he was “going over.” He was 46. It is indicative of the situation in England then that in the same year, 1947, Jackson Pollock lassoed the first paint onto a canvas he was later to call Cathedral: a topological gesture that lay waste the whole Euclidean landscape in which Circle had stood as a beacon. But dazzled by the light of his Pauline conversion Pasmore was not to notice that!

We should be glad, I think, that he thus missed the mainstream. True, much of his polemic has sounded old-fangled, but he has a superb sensibility that triumphs in the most quixotic tight corner. The present works, with their unhappy eclecticism, do him less than justice. He is at his best in a piece like Brown Development, with its breath-taking poise and subtle play of illusory space and light.

Nicholson’s most direct influence was once on Lanyon, whose work around 1949-52 pays homage both to Nicholson’s classical intention and his austere richness of surface. Lanyon’s output, however, like Heath’s, Davie’s, Wynter’s and Heron’s, changed radically in the early 1950s, under the impact of the United States.

Until then, Heath and Davie had been concerned with abstractions rooted in geometry. Heath, indeed, had followed Victor Pasmore through his figurative period and undergone a similar conversion—even writing a book to explain the new convictions that he was in turn to move away from—whilst Wynter and Heron were figurative, the latter owing a good deal to Braque.

Scott, Frost, Hilton and Vaughan (whose earlier work has a touch of Sutherland about it) were caught by similar currents, including some from Paris, but their rate of change has been less revolutionary.

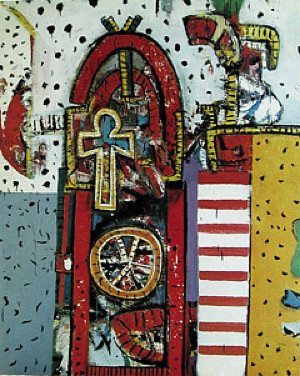

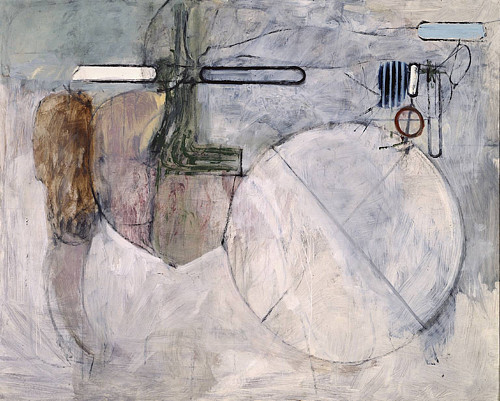

Frost has changed least on the evidence here, although sometimes his brush has moved like Lanyon’s. Hilton, who has discarded very little in terms of style over the last ten years, has been forced to make a theoretical adjustment: once he was adamantly non-figurative—his pictures were not “vehicles for images.” However, allusions began to filter through, perhaps from the French painter Dubuffet, as in this work, in some cases to propel him into the arms of the landscape tradition, as his December 1963 shows. Admirers of this picture will not be surprised that, as the exhibition opened in Toronto, Hilton was winning the main prize at the annual John Moore’s Exhibition in England (whilst, in 1962, this highly-competed-for prize had been awarded to Henry Mundy). Mundy, although he matured later than others here, has a formidable talent. You might say that he makes a sort of rococo to Davie’s baroque.

Where Davie is strident and lustily mischievous, Mundy is melting and restrained—languorous where Davie is ejaculatory. About much of Davie there is a gargantuan aggressiveness. He is like Rubens, always bursting at the seams. His best canvases are emblems of procreation; his viewers must run a gamut of ovulations, copulations and gestations: we let go, there is a kaleidoscopic rush, and we land, bawling heartily, with each new canvas, to look back in surprise at the mysterious door that has closed behind us (significantly, Davie’s painting here is called Entrance to a Red Temple). But Mundy’s world remains amniotic, safe. His forms migrate to the centre of the canvas, his membranous surfaces and milky light give reassurance (in spite of the title of one work called Mine, which creates a bizarre tension between what we see and what is implied by such a word). Yet such analogues come from no conscious intention.

Mundy’s scratched and scrabbled lines and marks, veiled by thin washes or the sudden impact of opaque lacquer, are in the end his only realities, and nothing is framed by the painter’s marks; rather the marks themselves are directed by a latent dream, which perhaps takes place in us as we explore their surfaces. The tension, between execution and evocation, thus set up is a measure of their achievement.

This was the first British Council show in nine years to travel through Canada; even so, some of these painters appeared for a second time (in fact a show called “Six Painters from Cornwall” traveled through Canada in 1955). One may hope that their reappearance today, however acceptable in itself, does not signify a failure of nerve. Britain has much still to show and it is the Council’s duty to see that it is shown more frequently and, certainly, much more comprehensively.

Addendum:

(The following notes enlarge on the backgrounds of 9 of the 14 painters discussed above)

Benjamin (Ben) Nicholson (1894–1982) was the son of Sir William Nicholson, a celebrated portraitist and a graphic designer central to the English version of Art Nouveau (his graphic works were produced in collaboration with his brother and they signed themselves the “Beggarstaff Brothers”). Sir William’s son Ben was thus brought up at the centre of a cultured élite that included such figures as Ellen Terry, the most distinguished actress of her day, and her son Edward Gordon Craig who revolutionized stage design throughout Europe in the first decade of the 20th century.

Ben, who chose to follow his father as a painter, gradually turned in his late ‘twenties towards synthetic cubism and then to Mondrian and Russian Constructivism, especially after the arrival in England of the exiled Russians Naum Gabo and Anton Pevsner, though his work could never be confused with theirs. By 1937 he was the organizer of Circle, a book-size formalist manifesto by the small group that surrounded him. In 1938 he married his second wife, Barbara Hepworth, a sculptor more obviously influenced by the Russians (as well as by their friend, the sculptor Henry Moore). They lived much of the time between London and an exotic small seaside town, Saint Ives, in Cornwall, where a colony had existed since 1920 around the ceramicist Bernard Leach—who had returned from several years in Japan to revolutionize Western ceramics. Both Nicholson and Leach were to become international celebrities, such that Leach was to become a Companion of Honour to the Queen, and Nicholson was to receive the highest honour that Britain has to offer: the Order of Merit.

In1936, just prior to Circle, Nicholson’s work had been featured in Cubism and Abstract Art, Alfred Barr’s groundbreaking exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, and after World War II, he consolidated his international reputation by winning, among much else, first prizes for painting at the 1952 Carnegie International, the 1954 Venice Biennale, the first Guggenheim International, in 1956, and the 1957 Sao Paulo Biennial. In 2013 a painting of his at auction made $3,500,000.

Graham Sutherland (1903–1980), a contemporary of Nicholson’s who was also awarded the Order of Merit, preferred landscapes and plants, often with uncanny distortions. Thus he became the only painter in the present show whose work had appeared in London’s International Surrealist Exhibition of 1936 (however, at the end of that year Alfred Barr, at MOMA, installed a much larger and more comprehensive Surrealist exhibition, twinned, as it were, though separate from, his earlier Cubism and Abstract Art, alas, without Sutherland!). Sutherland, however, had converted to Catholicism (hence his interest in thorn trees), became a war artist during World War II and in subsequent years was to receive several commissions for major works during the restoration of war damaged churches. He was also commissioned to paint the portraits of certain members of the War Cabinet, one of which (that of Winston Churchill) was so disliked by the sitter that it was destroyed by his wife!

Victor Pasmore (1908–98) may be said to complete the trio of older artists in the show who received the above mentioned British honours (he became a Companion of Honour), and were, all three, in time, represented by the Marlborough Gallery. Pasmore, however, was neither an abstract artist nor a Surrealist. While Sutherland was showing in the 1936 British Surrealist Exhibition, Pasmore joined a small group of figurative painters who called themselves “The Euston Road School,” a group who created delicate figurative works with careful scaffolding such that after the War led Pasmore to “go over” in favour of abstract works like those of his in the present exhibition, works that he promoted from 1952 for the rest of his life. Indeed, from 1952, through his teaching at Newcastle-on-Tyne, Pasmore became a leader in a movement that from the mid ‘fifties onwards attempted to reform English art colleges somewhat after the manner of the Bauhaus of thirty years earlier—a movement which, ironically, though it actually did dragoon the government into radical reforms, was by then so retardataire that successful British artists of the next generation, in the 1960s, owed little to it.

It is significant that four of the remaining six artists were also associated with the village of St. Ives mentioned above as the home of Ben Nicholson and Barbara Hepworth. One of the exceptions is William Scott (1913–1989) who led perhaps the most interesting life of those in the show. A product of the Royal Academy Schools he migrated to Pont Aven in Brittany (the French equivalent of St. Ives, where Gauguin had briefly lived in the 1880s) and started a small school there while still in his twenties. After the war had intervened with that project, however, he became senior lecturer at Bath Academy. In 1953 he visited New York where he met Jackson Pollock and others and came back to give up teaching in 1956. His work evolved from figuration owing something to Bonnard’s to become increasingly more abstract—whilst retaining Bonnard’s febrile line.

Peter Lanyon (1918–1964), who joined Scott to teach at Bath Academy, was a gliding enthusiast who died when his glider crashed. He was actually born in St. Ives and briefly took lessons there from Nicholson. Sometimes one seems to see a reflection of his gliding hobby in the free, white brush marks on a blue ground, like the one illustrated here. He had a show at the Tate Gallery in 1956 and in 1957 visited New York where he met especially Mark Rothko, but his subsequent work shows such indecisiveness that one often feels it could have been created by different artists—though always with a sense that New York is somewhere in their background.

Bryan Wynter (1915–1975) also taught at Bath Academy and lived for a time in St. Ives where he became influenced by the American painter Mark Toby who was a long-time friend of Leach (see above) and was influenced by Leach’s intimate knowledge of Japanese calligraphy. One finds an echo of that calligraphy in Wynter’s work which, like Lanyon’s, owes something to the New York school too.

It remains to mention two more of the exhibitors who lived at some point in their lives at St. Ives. These are Roger Hilton (1911–1975) whose work frequently changed its direction and seems to suffer from a lack of conviction similar to Lanyons, and Patrick Heron (1920–1999) who, in St. Ives, became a friend of Bernard Leach and in 1958 actually bought Ben Nicholson’s house there. Like Nicholson, Heron had work in the U.S. Abstraction show of 1956. He also became a critic with frequent articles in the left wing British weekly The New Statesman and Nation, articles which brought him to a friendship with the American critic Clement Greenberg whose writings on “Post Painterly Abstraction” seem to have influenced his paintings, as seen here. He was so well respected that he became a trustee of the Tate Gallery, but turned down a knighthood offered him by the government of Margaret Thatcher as well as the offer of a membership of the British Royal Academy.

Alan Davie, (1920– ) who never lived in St.Ives, is at age 91 still painting cascades of colourful images, though now they are more controlled and somewhat reminiscent of primitive rugs. His work was well received in the USA and its painterly qualities seem to owe something to Jackson Pollock’s canvasses just prior to the beginning of Pollock’s famous “drip” paintings.